LAST NIGHT IN MARRAKESH

In my next life, I will be a man. One who runs before the bulls. In the narrow streets. Of Pamplona. No! I will be a man who does not run. I will stand in a broad arena and hold a sword, and with my cape dazzle the bull. After long minutes of turning and study, the bull and I will have a moment to consider. Then, I will thrust the sword into that part of his body that yields, the flesh just between the shoulders. The tip of the sword will slip straight through to the heart. The beast, on its knees, will make a bow and die quickly.

Hemingway said that a bull learns more in fifteen minutes than most men learn in a life time. Hemingway took a gun and put it in his mouth. When he pulled the trigger, what filled his brain? What hit the wall, the ceiling? What had he learned in his life time?

There was a real man. In my life time. I actually met him. In Las Vegas. I had gone to see him fight. I’d gone there with my (married) professor of Myth and Magical Thinking in World Literature. I fell in love with the professor first semester of my freshman year, and, of course, he noticed me. I have a strong intellect, and that is something he genuinely admired. I also have big brown eyes and, at that time, blood filled cheeks and line-free lips. My nose is perhaps a little too large but it’s on a scale with my eyes and my intellect. In spite of all my attributes, it was not until the second semester that I managed to find my way into his heart. I knew it would have to be through his mind, but he was so subtle it took me all those months to become aware of his intellectual weakness. That’s what I would attack.

The professor lauded the strength of all the male characters we studied, but he found that same quality sinister in the female characters. Mothers and virgins were fine. But a formidable independent figure, even if a deity, someone like Kali, for example, who hunted and destroyed egos…someone like that, he spoke of with disdain.

I wrote a paper that I knew he would give more than faint praise, but he’d want to point out some basic problem with my research or my reasoning. I need not describe the paper as the gist of it was in the title: “Mother Earth and Tangled Tresses - Feminine Sources of Strength for Antaeus and Samson.”

“Here’s your paper, young lady” he said, looking appreciatively into my eyes as he held my paper out to me. Just as I reached for it, he pulled it back, close to his chest, pretending to have had a spur of the moment idea: “If you have a little time after class, I’d like to talk to you a little about the thesis you’ve put forward.” My thesis indeed.

We ended up in his office where he explained the problems of my paper to me in language so pedantic and esoteric and lacking in punctuation (in its delivery) that I really couldn’t make any clear rebuttals. I simply knew I was being unfairly attacked and deeply desired at the same time.

“The male,” he explained “throughout history has not been animated by the anima but by the desire to overpower the animus as Father or to protect the animus as son.” He went on, naming hero after hero and strength after strength. “None of it,” he pointed out more than once, “had anything to do with anything feminine like ‘mothers or hairdos.’”

It had to be a man-to-man thing. “It continues today in only a few sports. Boxing,for example.” He now took on the relaxed smugness of the insider, part of a very hairy tribe: “We say some punches knock you out, but the important ones are the punches that knock you to.” I liked that idea, and, in spite of his posturing and pedantry, I genuinely admired him. Besides having fallen in love with him. He could see all that, and he was pleased to learn that I did, in fact, like boxing and other non-team sports. One on one. That’s what appealed to us.

When he took me to the fight, we had to be discreet, not only because he was married but because he was a little embarrassed that he liked boxing, and he had the absurd idea that he was well known. Someone might see him ring-side, take his photo and put it in the tabloids. He taught Literature for goodness sake, and he was not a writer like Faulkner or Hemingway. He wrote articles for obscure journals that universities subscribed to and hardly anybody read. I read his articles. I was fascinated really by everything he wrote and by his lectures. So were a lot of students, but news he wasn’t.

He could find ways to explain his love of boxing or the competitive or even violent things that spoke to his primal needs. I didn’t really understand him. I was obsessed with him and rather suspect it was some primal need of my own that demanded I win him. I think I wanted to kill him, or at least break his will. Whatever it was, I called it love.

When I was in Spain the first time, I was very young, and I’d gone to the plaza de toros every day for at least a month. I was enamored with the grace and style and courage of the matador. But the boxer’s courage, his style, his grace--his footwork alone---was more dazzling than any whirls or swirls of a matador’s cape, and the outcome was far less predictable.

I admired the fighter because he was not afraid to fight yet he would not fight in the war. He was punished for his stand, for his integrity. He startled people with his rapid-fire pre-rap poetry and in-your-face challenges, but he was clearly a champion, the champion we all saw float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.

I met him the night he defeated that strange guy who dressed up in disguises and, now and then, was arrested for drunk driving and odd misdemeanors. My married man had gained entry for us to the reception for the fighter that night. We had not sat together at the large table where he and his friends gathered for dinner. All of us pretended I was not with him. After dinner we did not stand in line together to shake the champion’s hand, and when it was my turn, the fighter apologized because he couldn’t oblige me with a handshake. I was young and flirtatious and a little out of control over this married man; maybe I was also a little drunk, so I said, “Why can’t you shake my hand? What have you been doing tonight?”

He smiled his mischievous smile, looked me straight in the eye and said, “Beating up little boys.” He has a space between his teeth that I don’t think I quite appreciated before this meeting. I bet he never had braces. Made me feel as though he had some extra sort of freedom represented there. “Beating up little boys,” he repeated, tickled I think with what he was saying. I was tickled too. It was a great moment in my life and one that contributed to that tiny but fulsome seed within me that said I could be a champion, a winner, at something. Make a name for myself. I could have power, not mere brute strength but power like this man’s. .

That’s what I think, but what do I know. I am a woman who has not risked much since I risked fighting for the married man. This was my main event. It left me on the mat.

A girl on assignment for our on-line high school newspaper was interviewing me, her video camera in hand. The occasion was my retirement, which was a little more news-worthy than most retirements because I was so young, only 41. I wanted my freedom, figuring twenty years was enough. Now it was time for something new.

I had learned over those twenty years to deal with the cheekiness of teenagers and I was practiced in responding quickly and aptly to anything they might say. However, perhaps because of the camera or because of the freedom I was anticipating, I felt as if I were in a foreign land, talking to a stranger, the kind you tell your secrets to because you know you’ll never see him again. Whatever the reason, I dropped my guard. When the girl’s question came, I answered spontaneously and a little too honestly.

“What,” she asked, “is the one thing you did not do in your life that you regret?”

“I did not run before the bulls in Pamplona.” I heard my words and felt the racing of my heart. I hoped I was not blushing.

She heard my words clearly but could not make sense of them. I’m sure she could not imagine me running at all, much less in front of bulls, much less somewhere that was possibly beyond our beloved campus. I told her it happened in Pamplona--that’s a city in Spain, north of Madrid. Nothing I’d said had made things easier for her. She was still dumbstruck, so I dutifully turned to the camera and asked myself, “What was it?” Dutifully I answered, “My failure to run before the bulls.” By this time, I had caught up with myself and would reveal no more, but I clearly saw in my mind’s eye the Dear Jane letter that I’d held in my hands just after I failed to run before the bulls. The letter from the married man. I certainly wasn’t going to say anything about that.

The girl was still frozen. I waited. Finally, she stirred and without segue moved on to other subjects, the ones I call “my favorite colors.” We were both happy with that and stayed safely in that zone to the end of the interview. When it was over, my heart began to race, again. I could not help but recall how confident I was when I arrived in Spain, sure of myself and sure of the professor.

After the interview, I went home and called a travel agent. I told her I wanted to go to Spain, explaining that I’d been there before and wanted to see new places, have an almost entirely new experience. She told me about a motor coach tour of Spain and Morocco. North Africa! I would go to Madrid, where I’d been before, but then I’d see the Al Hambra in Granada and flamenco dancers in Seville and, beyond anything I’d have thought to ask for, I would go to North Africa, to Morocco and I would…what? I didn’t know, but I knew I would see or do something extraordinary.

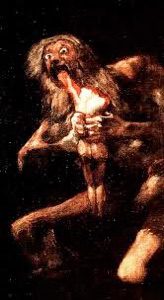

MADRID: I didn’t feel compelled to do much in Madrid, except to revisit some of the places I had discovered as a youth. The highlight then had been the Prado, especially the section they called “The Masters.” It was easy to miss something but how had I managed to have never before seen, not even in a book, the grotesque painting of Saturn Devouring his Child? I’d read that Goya had been very affected by the prospect of death during his last years on earth. What better time, I suppose, but why? There was no percentage in dwelling on the inevitable; in fact, you’d only be encouraging it. Why not live? I laughed at myself, meanly, as it was becoming clearer and clearer to me that all those years of teaching were possibly just a way of killing time.

I’ve never had children. Just my students. Well, there were many occasions,when I encountered parents who devoured their children, especially mothers, who nibbled away while they kissed and patted and whispered fear into their children, especially the girls, “for their own good.”

The painting had to have been there the first time I came to the Prado, but I didn’t remember seeing it at all. Now I could hardly move away from it. A gnawing fear of death? It was simply too literal. But why was Saturn eating a child, his own child? I shuddered and moved on.

AVILA: All out of balance was the chapel of St. Teresa in Avila. I was irritated by the ostentatious show of gold around the statue of this modest saint. I feel a certain respect for the dead, and she was a reformer of the opulent life style the clergy had adopted. I recalled a photo I’d seen in a book of religious sculptures. St. Teresa was swooning. An Angel had pierced her with a spear. It was a depiction of one of her great ecstatic moments with God which she described as a great pain and a great sweetness, a caress.

As I remember it, the Inquisition almost put an end to Teresa, but someone, a King I think, intervened. I love the thought that it took great mounds of money and power to keep her in poverty. I would think about this chapel again when I encountered the beggars in Seville.

PAMPLONA: About the bulls. I’ll tell you now.

I had arrived in the city feeling very free and ready for anything. The night before the running of the bulls, my spirit of adventure was slightly inflated by the spirit of the grape. We--the other young people and I who had come to experience the Hemingway heart of Spain--had all had a little too much to drink, and we eagerly made our mead-hall promises to run before the bulls the next day

In the morning, though, I woke up with a bit of a hangover. It got considerably worse as I sat in the stands remembering my promise. I looked across at the balconies full of young men readying themselves. My temples began to throb, and I could feel panic numbing the back of my head. My mouth was cotton, and my legs would hardly support me as I took a few slow steps down the stairs and then over to the group of men at the balustrade. They did not easily make room for me to find a place for my hands on the railing. Once I did manage to curl my fingers around the rail, my hands were frozen to it. I did not belong here, not just because I was a woman but because I was terrified of what I was about to do. They might have been terrified, too, but they were laughing and singing and hitting each other with soft fists of affection. I would not have been able to say a word or do anything in the least convivial even if they’d wanted me to.

Then came the moment. There was no mistaking it. I heard the yells coming from the top of the street. Then I heard the hooves and understood in the weakness of my legs and the rigidity of my arms what panic actually feels like. Death was thundering down the street toward me. They were here, now. One more second. I bent my knees and my legs nearly collapsed, but I kept them there, trembling, readying myself to leap…when I heard someone yell from the street, “Atencion.” It was a Spanish policeman yelling and he was yelling as me. His arm was lifted high and he was wagging his finger at me. “Atencion,” he said. “mujeres, no!”

“Mujeres, no?” I cried in indignation. “Porque no?”

I don’t know what his answer was and it didn’t matter. What mattered was that I would not have to--actually wasn’t allowed to--jump. I turned on my heel, my body suddenly strong and sure, and I mumbled a convincing outrage as I climbed up the stairs to my seat. I looked back down to the balustrade. All the men had jumped. They did it. I sat down trying to not feel grateful, trying to avoid the truth, but it came: I was not brave. I was nothing. I was nothing but a woman.

When I got back to the pension, I saw there was a letter waiting for me. It was from the professor. Someone had picked up my mail from American Express. Salvation, I thought, tearing the letter out of the envelope.

“My dearest,” he wrote, “I have decided, for the sake of my career, to attempt reconciliation with my wife. I do not regret a moment spent with you. I will always care for you, and hope this is not a blow, but if it is I hope you find the strength--the animus within you--to understand and to recover quickly from any hurt I may be causing you. Hope you have a wonderful time in Spain.” Animus! He had the nerve to use my own argument against me, to use Latin even while he broke my heart, to use his career as an excuse to dump me. Nobody cared about his marital status any more than they cared about his going to Las Vegas. Oh, I went into a rage, all right, and I was using nice short descriptive Anglo-Saxons words. It wasn’t long, though, before I realized it was not the professor I was yelling at. I was the one, even less than a mere inferior being in a world of men. I was the coward.

By the next morning something leaden had fallen into my broken heart and it stayed there all this time…until this time, this trip. Until my last night in Marrakesh.

SEVILLE: The beggars sat just outside the Cathedral at the Door of Forgiveness. They sat very still on the frozen ground, frozen themselves, sitting as still as the statues looking down on them. As I approached the door, they extended their hands, open and outstretched, palms up. It was then the gold from St. Teresa’s Chapel came flashing back to me. These beggars weren’t asking for gold, and I had a great urge to put something into their hands, yet I could not bring myself to give them money. What then? We did not see a bull fight or Spanish dancers. If it weren’t for the beggars, I might not have remembered we stopped in Seville at all.

MORROCO: A trip to the Medina. We had a new guide for this portion of our trip. An attractive man. Our first stop was just outside the old walls which I hardly noticed as I was so enthralled by the huge birds sitting on top of the walls and on the rooftops of nearby houses. The birds looked like pelicans except that their beaks were shorter, sharper, and more pointed.

“Those birds you see” our guide was speaking to us, “are storks. They used to visit us only two or three months of the year, but lately large numbers of them stay year-round. The ones that do leave return to the same nests the next year. They are attached to Marrakesh. Who could blame them?” He smiled, a really disarming smile, and looked at me. “In Ancient Egypt these storks were associated with the human soul, the ba, the unique character of each human being.”

I surprised myself by responding to this stranger (and in front of all the strangers around us) in a somewhat flippant way: “I’m sure you know that we believe storks bring babies to us. In Sweden they say the number of babies born is highest when storks return.”

He liked that. “No other cause?”

I liked that. “None.”

The bus dropped six of us off to go on a walking tour with the new guide. Just after he’d assembled us in the square, he warned us not to lose sight of him once we went into the Medina. He joked about the tourists in the souks who, last year, strayed off and had not been seen or heard from since. It did seem entirely possible that without a guide I would never find my way out. Maybe I’d even be kidnapped. A ridiculous thought. But that world was exotic, something apart from any experience I’d known. It was not rife with history. It was history. It was a thousand years ago. No ransom could reach anyone here.

The square just inside the walls was full of people, hundreds, maybe thousands. One part of it was devoted to performers: acrobats, snake charmers, people with trained monkeys, though there seemed to be a lot of wild monkeys racing around as well. There were dancers and singers and musicians, but it all seemed hokey to me. There was one group of men who did interest me: the water sellers. They carried large leather pouches of water slung over their shoulders. Their costumes were from some distant century. Their hats looked like sombreros, black with red and gold tassels. And the men were in constant motion. People had to catch up with them and make them stop so they could buy some water. It tickled me. Reminded me of kids running after an ice cream truck.

“Would you like some water?” I turned and saw it was the tour guide. I smiled and shook my head and looked back into the square, away from his penetrating brown eyes and his quick smile. He bore a really strong resemblance to the prize fighter. He had a space between his teeth like his, and he had that same mischief in his eyes and the same smile around his eyes, and the North African robe he wore had a hood on it very much like something a boxer would wear. The color of his robe was fitting, too. It was purple, the color of royalty. Of someone great. The greatest.

He repeated, “I’d be happy to get you some water. Introduce you to one of the water sellers.”

“No. No, thank you. Their hats, the tassels. It’s all so historic, so enduring, your culture. I see it in the water sellers. It’s so strange to me. So interesting.”

“More interesting than the snakes and the monkeys and the acrobats?”

“Funny, but, yes, to me they are.”

“You are funny to me,” he said. “Strange and interesting.”

I didn’t know what to say. I might have blushed, but I’m not sure. I was sure that I needed to distance myself from the guide for a few minutes.

“I’ll be right back,” I said as I turned and walked a few steps over to a shop that sold jewelry and small mirrors and some odd things I wasn’t sure of. I feigned great interest in the shop’s contents, and that attention brought something peculiar to my sight. It was a flat piece of bright metal shaped like a hand, and it had a turquoise eye in the middle of it. I’d seen something like this on Buddhas, I thought, but these were different, not connected to anything. Just these flat hands hanging like pictures on a wall.

A woman wearing a head scarf and a small black veil across her face took one of the hands and placed it in mine. It was cold and sharp. Then she gave me a piece of paper that had been cut out of a book. It said something to this effect: In some countries along the Mediterranean there are apotropaic phalluses, sculptures or drawings, and something like apotropaic hands, suggesting perhaps a vulva, hammered out of silver or copper or tin. These are meant to protect you from the evil eye. However, the vulva, it is thought, as a symbol of female power, is a dangerous and threatening thing, so it is stylized into a hand.

And I thought: Why fear the vulva? If there is an organ to fear, one full of raging needs and violent demands, is it not the phallus? I handed the paper and the metal piece back to the woman and thanked her. I wanted to buy it, actually, but I didn’t understand the money yet, how it compared to dollars, and I also didn’t have much of it, and I really didn’t understand why I’d want a thing like that. I turned back around, empty handed, and joined my group.

The noise and smell of the place pressed us all very close to each other in the dim light that gathered beneath awnings and plastic tarps that stretched across from one side of the walkway to the other, creating a canopy overhead. What gave me the courage to enter that world, I do not know, because even the donkeys as they pushed their way past me, frightened me.

.

The colors of the spices, piled in pyramids, were the same as the colors of the carpets displayed on the walls. Turmeric, saffron, anise. Ochre, red, black. I bought a long skirt and light sweater. They had all three colors in them. The guide, I felt his eyes on me, approached. He had a pair of earrings in his hand.

“These will look nice with your sweater, I think.” He held out his hand. His palm was very pink, as if his hand were blushing. The earrings were gorgeous, exotic for me, very colorful. Yellow amber and turquoise. I took the earrings out of his hand as deftly as I could without touching his flesh. I’m sure he could see how deliberately I was avoiding that touch.

I put the earrings on and looked at myself in the mirror. I did not look like a school teacher. I was alive, vibrant, a little wild-looking. The shopkeeper told me the price in English but my uncertainty about the dirham and euros I held in my hand made me hesitate.

“May I?” the guide asked.

“Oh, yes. Thank you.” I stuttered part of that reply, but I held my hand out to him and he showed no compunction at all about touching my hand, moving the coins around so that his finger marked my flesh. “There,” he smiled, “they look wonderful on you. Beautiful.” And I felt beautiful. I felt desirable. I felt desired.

We turned into a leather shop. Shoes that were long in the toes and pointy, handbags and belts. Again the colors, the dyes coming from earth or bark or flower or fruit. The shoes were comfortable. I bought a pair the color of the Medina walls, red ochre. Then I went up the stairs to the second floor where there were jackets and coats and boots. I soon realized that I had been trying to ignore an exceedingly unpleasant smell which grew stronger once I acknowledged it. I felt uneasy and decided to go up to the top floor and join my group.

I spotted them standing in a doorway to a balcony. I walked over and stepped past them out to where there was more room to stand, but then I saw the reason they had kept to the doorway and the wall. The stench was nearly unbearable, but the shock was how high up we were and how steep and immediate the drop off was into what felt like a monstrous well or a quarry. I felt a little dizzy and tried to anchor myself against the railing. I felt it move. I looked down again, more closely, and saw that it was not a quarry, not rocks being carved but animals. Animal skins being cleaned and rinsed and dyed. I tried to steady myself by closing my eyes and turning my head up. “Madam?” It was the guide.

“I’m sorry. I was suddenly…”

“Do not worry. Sometimes young women are affected by the tanning.” He smiled.

The space between his teeth.

I smiled as best I could.

“Good. We will drink tea and view carpets. He leaned forward and whispered into my ear, “If you find a carpet that appeals to you, do not pay more than sixty percent of the first price he gives you.” His lips so close to my ear.

We entered the carpet shop through a low doorway that opened to a two or three story home. The central area had a small tiled fountain with several tiers that let the water cascade. The sound of the falling water soothed the remaining disturbance in my mind.

We were seated in low wooden chairs with finely woven cushions. All around and above us were balconies with carved windows. The guide gave us a short talk on Berber carpets and the processes involved in making them. I was far too interested in him to listen to the carpet lecture, but I tuned in again when he explained the odd windows that were partially covered on the second story balconies. In days gone by, young women stood at these windows and viewed the young men gathered at the central fountain for the express purpose of showing themselves. The men knew of course that the women were there. It struck me a little funny, sort of like a beauty contest with the men being the beauties and the women being anonymous judges. It seemed ultra modern, liberated.

The most expensive carpets were woven, knotted and embroidered. We started, however, with the carpets that were simply woven. I liked them, but it was the two process carpets--woven and embroidered--that brought out a completely new feeling in me. I would have to call it unbridled greed. I wanted that carpet. The design was simple, geometric shapes. . It also had lots of that dark yellow that should have not have been called ochre; it should have had a name more like musk., like the smell of a skunk 100 yards away; or mustard, something that burns the nostrils and sends subtle pains up to the top of one’s head.

“Only one thousand dollars for this beautiful tribal carpet. As you can guess, this two process work takes many months to weave and then many weeks to embroider. I will give it to you. Only one thousand.”

“Your tea, Madam.” The voice. I turned. It was the guide, holding a carafe full of tea. He smiled of course and looked into my eyes for just a moment before he poured the tea into my cup. I smiled and noted my hand was steady though my heart was beating rapidly. I snapped my eyes back to the pretty carpet and began to bargain. Too much. Too little. Can we compromise. I felt I was exasperating the man. I glanced at the guide. He was, I was sure of it, intrigued and surprised that I had so quickly taken to the game of bargaining. He could not have been more surprised than I was.

“Really,” I smiled, “I love the carpet. It’s beautiful, but it’s simply too expensive.

“This carpet pleases you, Madam.” I

“Yes, but I turned and started looking at other carpets, feigning interest.

“I think it’s just not the right time for me. Maybe we’ll have better luck tomorrow.” I turned to the guide. “We’ll have enough time to stop by here tomorrow, won’t we?”

His smile was different, with a question in it, but he answered evenly. “Yes, in the morning. We could stop here again.” He glanced away for a second, studying the carpet I had truly wanted to buy. Then he took a step back and said, “Do you make it a habit of not getting what you want?”

It was the carpet-seller’s turn to glance away. He was obviously suppressing a smile.

“And you!” I now focused my attention on the carpet-seller. “You cannot get me to pay a high price for a carpet, especially as I have seen nothing that I desire.” I thought I was going to leave the room, but found myself stomping over to the carpet I truly wanted, the red one with the triangles. “This one. I want this one, but I will pay you no more than half the price you asked for at the start.” I whipped out my credit card and offered it to him. “Half.” He took the card very slowly and carefully into his hand. “As you wish, Madam.”

Soft applause from behind me. I knew it was the guide. I refused to turn and acknowledge him, so I stood still where I was. Standing on legs that suddenly felt weak. I wanted to sit down. I wanted to cry from relief. Something remarkable had just happened and I didn’t know what it was but I liked it. I had wanted something and I got it. Maybe I had only got a fair price, but it felt like an amazing accomplishment to have bargained at all and then to have got I what I wanted.

“I want to show you something,” he said walking toward the balcony. I was silent, almost holding my breath, as I joined him. He wanted me to look out at the city. It was bathed in gold as the sun was setting behind us, casting light upon the buildings that turned the pale red ochre a vibrant pink. The poplars and olive trees and palms were purple, and a few stars were already glittering in the early evening sky.

Then he pointed out beyond the city. “You see the Atlas Mountains?” I nodded. “Crossing them can sometimes be treacherous. Beyond those mountains, to the south, is the desert, the Sahara. It took us centuries to learn the way of passage. We were studying it and all things even before the birth of Christ.” Here he stopped and smiled. “I had a speech prepared. It sounds false now. Let me start again.”

I was shocked to hear myself say, “You are asking me to cross the desert and the mountains with you this evening.”

A look of wonder filled his eyes and formed his smile, softly upon his face. “Yes. There is a gift I want to give you, something I wish to show you about yourself, something you have glimpsed, I think, in the short time we have spent together.”

“I have glimpsed it, but I don’t know what it is or why you offer me this…gift.”

“I also do not know, but I do not question it. Can you do the same?”

How easily I said the word: “Yes.”

He took me over to the long hall mirror. “You must see how beautiful you are.” He lifted my arms and pulled my sweater off as if he were unveiling a painting. He unfastened my brassiere. It fell to the floor. He kept all of his clothes on, even the purple robe. This was going to be for me, yet I heard his own excitement clearly in his breath, felt it in his hot hands. “Look!”

I hardly recognized the woman in the mirror. Her skin was so white. The dark hands that moved over her body, I did not know at all, but I knew they moved for this woman, for her pleasure.

“Keep your eyes open. Look at your beauty.”

He kissed the back of my neck and bit gently into my shoulders, piercing straight through to the heart of my most intimate self.

“No,” he said, “don’t close your eyes. See what it is you are feeling. Look.”

I could feel his heart, his entire body, pulsing against my bare back. “And you?” she asked in a whisper.

“First, the gift.”

“Look,” he said.

I looked.

I will not tell you more. It’s mine to keep. I can tell you that it was the first time in my life that I knew ecstasy. I saw it and I felt it at the same time. My guide moaned when I moaned, but when I cried out, I heard no other sounds, and I didn’t know who those people were in the mirror. I knew only this.

~ ~ ~

I did not want to sleep. I wanted to be conscious of how my body felt, was still feeling, but I could not resist, and I slept for at least an hour after he left.

When I woke up I was hungry. I showered but I did not change my clothes. I wore that sweater and that skirt and those earrings. I looked in the mirror. I was still there.

I reached the dining room just as they were beginning to serve dessert. I did not look around for the guide. I knew he wouldn’t be there. I was seated and served, a special Moroccan dinner, and I ate everything on my plate.

Then came the evening’s entertainment. Much more interesting to me now than they could possibly have been this morning on the Square were the musicians and singers and dancers and acrobats. The last act was a snake charmer.

The flute and the cobra were astonishing, beautiful and terrifying in their attention and response to each other. After a minute, the snake charmer held the cobra out to the audience asking if anyone wanted to handle it. It moved across his hand and then along his arm and around his shoulder. A tourist, a young man sitting close to the stage, stood up.

“Sir? Do you dare to take the cobra in your hands?”

“I am a policeman in Columbia. I dare.” With swift intensity, he took the snake by the head and then stood quite still as it coiled around his stomach and chest. He seemed nailed to the floor rather than standing on it. He was afraid, but he was standing there. He did not run.

I left my table and moved toward the stage. I had to see. But I was too late. The young man was handing the snake back while I was still too far away to see much. I was about to return to my table when the snake charmer produced a scorpion. He held it on his open palm and then passed it over the audience like a blessing.

“Who will come up and take the scorpion?” he asked.

I felt my breath go out of me as I heard myself say, “I will.”

He apparently didn’t hear me. He repeated, “Who will take the scorpion?”

My heart now pounding at my temples, I raised my voice. “I will.”

A current pulled me forward toward the stage.

He saw me now and quickly looked around. Did he want someone to stop me? Was he just making sure everyone was aware that I was approaching him?

I heard someone gasp, but I think no one moved.

He then looked away from me and spoke to the audience in a voice that sounded dull and distant. It surprised me. I stopped and listened. “Scorpions in Morocco are responsible for the deaths of at least 100 children every year. Adults, too…” I became impatient and started to move forward again, wending my way through the tables nearest to the stage.

“Madam?” he said, holding the scorpion in his palm.

I stopped again and steadied my eye on the scorpion. It was a shiny brown color. The tail was long and wide and arched up and over its body, making it appear to have two heads, one just an inch or so above and slightly back from the other. The barb at the end of its tail could pierce the flesh of almost any animal, certainly the unprotected flesh of a human being.

“This particular type of scorpion,” the snake charmer continued, his eyes darting back and forth from me to the audience and then back to me, “is called a “Death Stalker.”

I placed myself on the stairs. There were only a few more and then the stage would be mine. My legs felt strong under me. My heart was thumping in my chest and in my throat. I moved up to the top stair.

The snake charmer seemed frozen. I almost laughed. The look on his face was nearly identical to the look on the face of the student who’d interviewed me a thousand years ago in another world.

Maybe I smiled.

I stretched out my arm. My hand opened. I turned my palm up and stepped forward.

THE END